Avoid memory leaks in your Node.js apps

Closures are used in Node.js pervasively in various forms to support Node's asynchronous and event-driven programming model. By having a good understanding of closures, you can ensure the functional correctness, stability, and scalability of the applications that you develop.

Closures are a natural way of associating data with the code that acts on the data, with continuation passing as the main semantic style. When you use closures, data elements that you define within an enclosing scope become accessible to a function that's created in the scope, even when the enclosing scope is logically exited. In languages (such as JavaScript) in which functions are first-class variables, this behavior is of great importance, because the lifecycle of functions determines the lifecycle of the data elements that are visible to the functions. In this environment, it's dangerously easy to inadvertently retain much more data in memory than you expect.

This tutorial examines three of the main use cases in which closures are used in Node:

- Completion handler

- Intermediary function

- Listener function

For each use case, we provide sample code and indicate both the closure's expected lifespan and the memory that's retained during that lifespan. This information can help you design your JavaScript applications with insight into how these uses cases affect memory usage, so that you can avoid memory leaks in your apps.

Closures and asynchronous programming

If you are familiar with traditional sequential programming, you might ask the following questions when first trying to understand the asynchronous model:

- If a function is called asynchronously, how do you make sure that the code following it (or around it) can work with the data that's available in the scope when the call is made? Or in other words, how do you implement the rest of the code, which depends on the results and side effects of the asynchronous call?

- After the asynchronous call is made, and the program continues to execute code that's unrelated to the asynchronous call, how do you later return to the original calling scope to carry on after the asynchronous call is complete?

Closures and callbacks are the answer to these questions. In the most common and simplest use case, an asynchronous method takes a callback method (which has an associated closure) as one of its arguments. This function is often defined in-line at the call site for the asynchronous method, and the function has access to the data elements (local variables and parameters) of the scope that encloses the call site.

As an example, take the following JavaScript code:

function outer(a) {

var b= 20;

function inner(c) {

var d = 40;

return a * b / (d c);

}

return inner;

}

var x = outer(10);

var y = x(30);

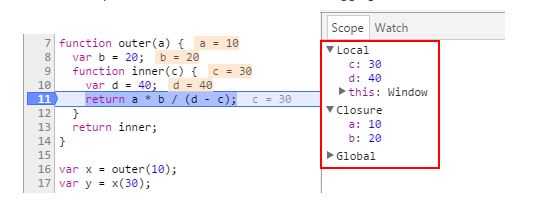

Here's a snapshot of the same code in a live debugging session:

The inner function is called at line 17 (line 11 in the preceding listing) and executes at line 11 (the listing's line 5). At line 16 (the listing's line 10), the outer function — which returns theinner function — is called. As shown in the screenshot, when the inner function is called at line 17, and executes at line 11, it has access to both of its local variables (c and d) and the variables defined in the outer function (a and b) — even though the scope for the outerfunction was exited when the call to the outer function completed at line 16.

“To avoid memory leaks, it's important to understand when and for how long the callback method remains reachable.”

The callback method is in a state in which it can be invoked (that is, is reachable from a garbage-collection point of view), so it keeps alive all of the data elements to which it has access. To avoid memory leaks, it's important to understand when and for how long the callback method remains in that state.

At a high level, closures commonly come into play in at least three kinds of use cases. In all three, the fundamental premise is the same: the ability for a small piece of reusable code (a callable function) to work with, and optionally retain, a context.

Use case 1: Completion handler

In the completion handler pattern, a function (C1) is passed as an argument to a method (M1), and C1 is invoked as a completion handler when M1 is complete. As part of the pattern, the implementation for M1 ensures that the reference that it retains to C1 is cleared after it's no longer needed. C1 often needs one or more of the data elements in the scope where M1 was called. The closure that provides access to this scope is defined when C1 is created. One common approach is to use an anonymous method defined in-line where the M1 is called. The result is a closure forC1 that provides access to all of the variables and parameters that are available to M1.

An example is the setTimeout() method. When the timer expires, the completion function is invoked, and the reference to the completion function (C1) that's retained for the timer is cleared:

function CustomObject() {

}

function run() {

var data = new CustomObject()

setTimeout(function() {

data.i = 10

}, 100)

}

run()

The completion function uses the data variable from the context in which the setTimeoutmethod was called. Even after the run() method has completed, CustomObject can be referenced by the closure that's created for the completion handler and isn't garbage-collected.

Memory retention

The closure context is created when the completion function (C1) is defined, and the context consists of the variables and the parameters that are accessible in the scope were C1 is created. The closure for C1 is retained until both:

- The completion method is invoked and finishes running or the timer is cleared.

- No other references to C1 occur. (In the case of anonymous functions, no other references occur if the preceding condition in this list is met.)

By using the Chrome developer tools, we can see that the Timeout object that represents our timer has a reference to the completion function (the anonymous method passed tosetTimeout) through the _onTimeout field:

While the timer is in effect, the Timeout object, the _onTimeout field, and the closure function are all held in the heap through one single reference to them — the timeout event that's pending in the system. When the timer fires, and the subsequent callback completes, the pending event in the event loop is removed. All three objects are no longer accessible and become eligible for collection in the subsequent garbage-collection cycle.

When the timer is cleared (through the clearTimeout method), the completion function is removed from the _onTimeout field and — provided that no other references to the function occur — it can be collected in the subsequent garbage-collection cycle, even though theTimeout object is retained because the main program holds a reference to it.

In this screenshot, heap dumps taken before and after the timer fires are compared:

The #New column shows new objects that were added between the dumps, and the #Deleted column shows objects that were collected between the dumps. The highlighted section shows that the CustomObject was present in the first dump but is collected and isn't available in the second dump, freeing 12 bytes of memory.

In this pattern, the natural flow of execution is such that memory is retained only until the completion handler (C1) finishes its job of "completing" the method (M1). The result is that — provided that the completion of the methods called by the application occurs in a timely manner — you don't need to take special care to avoid memory leaks.

When you design functions that implement this pattern, ensure that any references to callback functions are cleared when the callback is fired. In this way, you ensure that in terms of memory retention, expectations of applications that use your functions are met.

Use case 2: Intermediary function

In some cases, you need to be able to work with data in a more repetitive, iterative, and out-of-bounds manner, whether that data is created in an asynchronous or synchronous manner. For such cases, you can return an intermediary function, which can be called one or more times to either access the required data or complete the required computation. As with the completion handlers, you create the closure when you define the function, and the closure provides access to all of the variables and parameters that are available in the scope where the function was defined.

One example of this pattern is data streaming, wherein a server returns a large chunk of data and the client's data receiver callback is invoked for every chunk of data that arrives. Because the data flow is asynchronous, the operation (such as accumulation of data) must be iterative and occur in an out-of-bounds manner. The following program illustrates this scenario:

function readData() {

var buf = new Buffer(1024 * 1024 * 100)

var index = 0

buf.fill('g') //simulates real read

return function() {

index++

if (index < buf.length) {

return buf[index-1]

} else {

return ''

}

}

}

var data = readData()

var next = data()

while (next !== '') {

// process data()

next = data()

}

In this case, buf is retained for as long as the data variable is still in scope. The size of the bufbuffer causes a large amount of memory to be retained, even though this might not be obvious to the application developer. We can see this effect by using the Chrome developer tools, as shown in a snapshot taken after the while loop is completed: The large buffer is being retained, even though it will no longer be used.

Memory retention

Even after the application finishes using the intermediary function, the reference to the function keeps the associated closure alive. To allow the data to be collected, the application must overwrite this reference — for example, by setting the reference to the intermediary function as follows:

// Manual cleanup

data = null;

This code allows the closure context to be garbage-collected. The following screenshot from a heap dump, taken after data was set to null, shows that the manual nullification allows garbage collection of the retained data:

The highlighted line indicates that the buffer has been collected and its associated memory freed.

It's often possible to construct intermediary functions so that they limit the potential memory leaks. For example, an intermediary that allows incremental reading of a large data set could remove references to the portions of the data that were returned. But in these cases, it's important that this approach not pose a concern for other parts of the application that might have access to that data in a manner other than through the intermediary function.

When creating APIs that implement the intermediary pattern, be careful to document the memory-retention characteristics so that consumers understand the need to ensure that all references are nullified. Even better, if possible implement your API such that the data retained can be released when it's no longer required within the intermediary function.

For example, the function from the previous example in this section could be rewritten as:

return function() {

index++;

if (index < buf.length) {

return buf[index-1]

} else {

buf = null

return

}

}

This version ensures that after the large buffer is no longer required, it can be collected.

Use case 3: Listener functions

A common pattern is to register functions that listen for the occurrence of a particular event. Though extremely handy in asynchronous programming, this registration causes the listener function to "escape" into the event emitter's internal cache along with any associated closure context. This is fine as long as the events are being generated and processed, and the event interceptor module knows when to stop event emission and clear the listeners. The risk arises when the lifecycle for a listener function becomes indefinite or unknown by the application. As such, listener functions are most at risk of causing a memory leak.

“Listener functions are most at risk of causing a memory leak.”

Most streaming/buffering scenarios use this mechanism to cache or accumulate instantaneous data that's defined in an outer method, while the access is done in a closure function. Consider this example:

var EventEmitter = require('events').EventEmitter

var ev = new EventEmitter()

function run() {

var buf = new Buffer(1024 * 1024 * 100)

var index = 0

buf.fill('g')

ev.on('readNext', function nextReader() {

var byte = buf[index]

index++

process(byte)

});

}

Memory retention

The following screenshot, taken after the call to the run() method, shows how the memory is retained for the large buffer, buf. As you can see through the dominator tree, the large buffer is kept alive because of its association with the event:

The data retained by a callback function (listener) is held alive, even after all of the data is read, not to mention the fact that outer function has long returned. Because the function (nextReader) accesses the buffer, a closure context is created and maintained in the runtime, which will be cleared only when the function is detached from the event and no longer referenced.

// Once the purpose of ‘readNext’ event is met,

// remove the event from the Emitter

ev. removeListener(‘readNext’, nextReader);

The risk arises when you install listeners whose lifecycle is:

- Neither in your control nor fully known.

- Under your supervision and control, but the closure is anonymous, making it infeasible to reference and remove.

While the Node core libraries implement a number of event emitters (such as streams) and their consumers (such as http), their lifecycle definitions are well known. Similarly, when designing applications and library modules with event emitters and event consumers, you should take the time to understand the behaviors described above, and ensure that the lifecycle of the events is well defined and that they can be de-registered when no longer needed.

“When registering functions as listeners, make sure that they will be de-registered at an appropriate lifecycle phase of the application.”

A well-known example of this use case is a typical HTTP server implementation:

var http = require('http');

function runServer() {

/* data local to runServer, but also accessible to

* the closure context retained for the anonymous

* callback function by virtue of the lexical scope

* in the outer enclosure.

*/

var buf = new Buffer(1024 * 1024 * 100);

buf.fill('g');

http.createServer(function (req, res) {

res.end(buf);

}).listen(8080);

}

runServer();

Although this example shows a handy way to use the inner functions, note that the callback function — and hence the buffer object — are alive for as long as the server object is alive. Only when the server closes does the object become eligible to be collected. You can see in the following screenshot that the buffer is kept alive because of its use by the server request listener:

The lesson is that for any listener that retain a substantial amount of data, you need to understand and document the required lifespan for the listener and ensure that the listener is deregistered when it's no longer necessary. It's also advisable to ensure that listeners retain the minimum amount of data possible across invocations, because of their typically long lifetimes.

Conclusion

Closures are powerful programming constructs for achieving binding between code and data in a more flexible and out-of-bounds manner. However, the scoping semantics can be unfamiliar to programmers who are used to older languages such as Java or C++. To avoid memory leaks, it's important to understand the characteristics of closures and their lifecycles.